JOURNALS || Health & Medicine Blog (ASIO)

Global Green Betrayal: How the World Learned to Talk Climate While Letting Forests Disappear

Abdul Kader Mohiuddin(M. Pharm, MBA)

Alumnus, Faculty of Pharmacy, Dhaka University

Dhaka, Bangladesh

ORCiD: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1596-9757

Web of Science ResearcherID: AAY-1094-2020

SciProfiles: 537979

Email: trymohi@yahoo.co.in

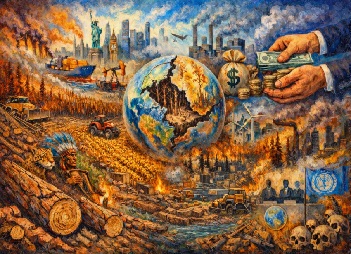

The world is not sleepwalking into deforestation; it is charging toward it with eyes wide open. According to Global Forest Watch data derived from the University of Maryland’s GLAD Lab, the planet lost approximately 6.7 million hectares of tropical primary forest in 2024 alone, the highest level recorded in more than two decades. That loss—nearly double the previous year-occurred at a pace equivalent to 18 football fields every minute. Roughly 95 percent of all deforestation now occurs in the tropics, regions that contribute least to global consumption but absorb the heaviest ecological and social costs. Despite decades of climate pledges and summit declarations, deforestation continues to account for aroundone-fifth of global greenhouse gas emissions, steadily eroding the credibility and effectiveness of every commitment made under the Paris Agreement.

At the core of this crisis lies the consumption footprint of wealthy nations. A landmark Nature study shows that high-income countries—including the United States, the United Kingdom, Japan, China, Germany, and France—outsource biodiversity loss at 15 times the rate experienced within their own borders, effectively exporting environmental destruction while preserving domestic green reputations. Demand from the United States and the United Kingdom alone accounts for roughly 13 percent of all forest loss occurring outside their territories, driven primarily by imports of beef, soy, palm oil, timber, and paper.

This reality is routinely obscured by narratives of “commercial-grade” agriculture, yet large-scale commodity production—driven by demand for beef, soy, palm oil, timber, and paper products—accounts for more than 80 percent of global deforestation. These are not accidental outcomes; they are structural features of global trade that reward distance from damage.In South America, for instance, a region responsible for producing a quarter of the world’s beef, cattle production increased by 70% between 1990 and 2020, while 90 million hectares of degraded pasture continue to fuel deforestation, according to another study in Nature.

Finance has enabled deforestation on an industrial scale. According to Global Canopy’s Forest 500 Finance report, in 2024, 150 of the world’s largest financial institutions funneled nearly USD 9 trillion into sectors directly linked to forest loss. At the corporate level, Global Canopy identifies nine forest-risk commodities—beef, leather, soy, palm oil, timber, pulp and paper, cocoa, coffee, and rubber—that account for more than two-thirds of global deforestation, yet most major companies sourcing these commodities still lack credible commitments to deforestation-free supply chains.

Political gridlock has further exacerbated the crisis. For instance, the EU’s Deforestation Regulation, intended to hold supply chains accountable for forest loss, has faced repeated delays since its approval in April 2023. These setbacks stem from pushback by the U.S., major commodity-producing nations, farmer protests, the ongoing war in Ukraine, and resistance from a right-wing majority in the European Parliament—turning enforcement into a process of postponement rather than protection.

Climate-driven and human-caused wildfires are now acting as powerful accelerants. Scientific assessments published in Earth System Science Data show that climate change has made extreme fire conditions 25 to 35 times more likely in some regions, locking forests into a self-reinforcing cycle of degradation, drying, and combustion.While some ecosystems experience natural fires, tropical forest fires are largely human-induced, often deliberately set to clear land for agriculture and frequently spreading uncontrollably into surrounding woodlands. In Indonesia, for example, roughly 60% of forests burned between 2015 and 2016 were later converted into palm oil plantations, highlighting the direct link between fire use and land conversion. Similarly, in parts of Africa, landowners often set fires on or near their properties to expand pastureland, further driving deforestation and landscape degradation. According to GLAD Lab and WRI, fires accounted for nearly 29 percent of global tree-cover loss between 2001 and 2024, but in 2024 alone they were responsible for almost 45 percent of total forest loss, nearly quadruple the share recorded just one year earlier. These fires released over 3 gigatones of greenhouse gases—surpassing the annual emissions of India.

Tropical primary forests were particularly hard hit, with fires accounting for nearly half of all loss in 2024. Brazil bore the brunt of forest loss, shedding an area comparable in size to Belgium or the U.S. state of Massachusetts, primarily due to extensive wildfires. Meanwhile, Bolivia experienced a staggering 200% increase in primary forest loss, exceeding the size of Montenegro and driven largely by fire rather than the agricultural expansion that dominated previous years. In the DRCongo, primary forest loss surged by about 150 percent in 2024, with forests shrinking by an area roughly the size of Delaware, fueled by a deadly mix of conflict, fires, artisanal mining, and governance breakdown.

Miners worldwide are locked in a fierce race for mineral wealth, forgetting that the true treasures lie in the lush greenery of nature—nurturing biodiversity for centuries and sustaining human life itself. While global leaders speak loudly about protecting the planet, their actions suggest otherwise: in the name of progress, they continue relentless extraction, treating some of the world’s poorest lands as expendable.Analyses by WWF and the World Resources Institute show that mining is now the fourth-largest direct driver of deforestation worldwide, and when indirect effects—such as roads, settlements, and power infrastructure—are included, it affects up to one-third of the planet’s remaining forests. Since 2001, mining activity has expanded by more than 50 percent, permanently clearing forest areas comparable in size to entire countries. A World Wildlife Fund (WWF) report shows that gold and coal extraction alone accounted for more than 70 percent of all mining-related deforestation between 2001 and 2019. Although just six countries—Russia, China, Australia, the United States, Canada, and Indonesia—were responsible for over half of global mining-linked deforestation, much of the extraction itself is concentrated in poorer regions, including the Amazon Basin, the Congo Basin, and Southeast Asia.The European Union exemplifies this imbalance, importing roughly 85 percent of its deforestation footprint while capturing most of the economic benefits at home.

Mining lays bare the contradictions at the heart of the global green transition. This pressure on forests is intensifying as geopolitical competition over critical minerals accelerates. China has financed roughly $57 billion in mining projects across 19 low- and middle-income countries, while the United States has rushed to forge partnerships across Australia, Japan, Malaysia, and Southeast Asia, framing them as supply-chain diversification while countering China’s dominance. The European Union has followed suit, channeling substantial funds into the same scramble for resources. Between 2001 and 2020 alone, mining drove the permanent loss of nearly 1.4 million hectares of tree cover—an area roughly the size of Montenegro—much of it linked to gold, coal, cobalt, nickel, and lithium, minerals increasingly marketed as essential to the “green” transition.

Mining-related conflicts have complex effects: in the Congo Basin, conflict occasionally limited mining, slightly reducing forest loss from 1990–2010. In contrast, Venezuela’s Amazon has seen illegal gold mining drive deforestation up 170% annually, clearing 140,000 hectares by 2023, as armed groups and military-backed operations ravage forests and exacerbate violence and environmental damage, according to an International Crisis Group briefing.

Armed conflict and post-war instability significantly accelerate forest loss, a factor often overlooked in climate negotiations. During the Vietnam War, millions of acres were defoliated with Agent Orange, devastating tree cover and critical food sources for local communities. In Gaza and the West Bank, the targeted destruction of olive trees has undermined livelihoods while deepening social and political vulnerabilities. Syria lost about one-fifth of its forests during the civil war (2010–2019) due to direct impacts such as fires from shelling, displaced populations relying on wood for fuel, and indirect pressures like poverty and weakened governance. In Myanmar, from 2021 to 2024, roughly 1.2 million hectares of natural forest—96% of tree cover in these areas—were lost, according to Global Forest Watch’s dynamic data.

In just two years of war with Russia, Ukraine lost nearly 600 square miles of forest—about twice the size of New York City—highlighting how quickly conflict can erode ecosystems. As natural gas supplies tightened and prices surged, households and industries across Europe increasingly turned to fuelwood and biomass. Some governments relaxed logging restrictions or fast-tracked timber auctions to stabilize energy markets, further straining forests. Rising energy costs, combined with EU bioenergy subsidies, have even driven households to burn wood in protected areas. Deforestation often intensifies post-conflict due to reconstruction, weak governance, and commercial logging. In Nepal, Sri Lanka, Ivory Coast, and Peru, annual forest loss rose 68% in the five years after conflicts—far above the global average of 7.2%—driven largely by illegal logging and agricultural expansion.

The socioeconomic consequences of deforestation are staggering. Research published in Nature finds that deforestation-driven erosion and chemical pollution contaminate soil, air, and water, contributing to an estimated 5.5 million pollution-related cardiovascular deaths worldwide in 2019. Another Nature study shows that tropical deforestation drives hazardous local warming, causing more than 28,000 heat-related deaths annually and exposing hundreds of millions—especially in Southeast Asia, Africa, and the Americas—to severe heat stress and sharply reduced safe working hours. The World Health Organization estimates that current deforestation trends cost the global economy roughly $10 trillion each year through higher healthcare spending and crop losses linked to declining pollinators, while the World Bank projects an additional $2.7 trillion annual loss to global GDP, with low- and lower-middle-income countries facing the greatest damage, including GDP declines exceeding 10 percent by 2030. Beyond economics, forest loss undermines food security for over 1.6 billion people and threatens the livelihoods and cultural survival of nearly 70 million Indigenous Peoples in carbon-dense forest regions.These costs dwarf the short-term profits used to justify deforestation, yet they remain absent from market pricing and political decision-making.

In light of this evidence, global climate governance increasingly feels hollow. Public trust has declined as U.N. climate summits are repeatedly held in major fossil-fuel-exporting and high-emission countries such as Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, and Azerbaijan. Amid numerous controversies, COP27 produced weakened outcomes, COP28 was chaired by the CEO of a state-owned oil company, and COP29 unfolded against a backdrop of human-rights concerns.Analysts argue that repeatedly hosting climate summits in countries heavily dependent on hydrocarbons and with high greenhouse-gas emissions undermines perceptions of the credibility and effectiveness of global climate governance.

While mother nature continues to nourish the Amazon with Sulphur-rich dust carried more than 6,000 kilometers from the distant Sahara, humanity continues to strip it of life. Between 2000 and 2018, the rainforest lost an area larger than Spain, and over the past four decades’ deforestation has consumed land equal to the combined size of Germany and France—driven by cattle ranching, soy cultivation, logging, mining, and unchecked expansion, leaving its biodiversity increasingly fragile. The backlash surrounding COP30 in the Amazon, where reports emerged of large-scale tree felling to accommodate summit infrastructure, crystallized global frustration. Also, the host region and state (Belém, Pará) are already weighed down by chronic deforestation, illegal gold mining, threatened Indigenous territories, and mercury-contaminated waterways. When a climate conference ends up contributing—directly or indirectly—to deforestation in one of the planet’s most vital ecosystems, the credibility gap becomes undeniable.

Our forests, the silent custodians of life, are disappearing at an unprecedented pace, driven by global warming, human greed, and relentless land-use change, as if the Earth itself mourns its own destruction. Humanity drifts helplessly in a tragic cycle of deforestation, blind to the irreplaceable gifts forests have nurtured for millennia, while evidence reveals a sorrowful tale of global green betrayal, where lofty promises of sustainability crumble under relentless tree loss. Deforestation—driven by agriculture, industry, mining, and conflict—destroys biodiversity and tears apart the delicate systems that sustain life, with climate-driven wildfires and irreversible land-use changes pushing forests past the point of recovery. This is the heart of global green betrayal: a world full of excuses, rapidly losing its forests, and turning a blind eye to the fact that survival requires not more promises, but urgent, enforceable action.

Hyperlinked

Published on: 12/01/2026